Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is an approach to curriculum design and delivery that caters for a wide diversity of learners. It is an evidence-based framework that promotes the right to education for all, with an aim for barrier-free inclusive learning environments. UDL applies to teaching in a similar way that universal design for the built environment ensures access features such as ramps, lifts and ground surface tactile indicators are considered from the point of design and available for all to use.

UDL is aligned with the philosophy of full inclusion where all classes are expected to be barrier free and able to cater for all learners (Blamires, 1999). Accompanying this approach is the intention for quality innovative pedagogy that is responsive to the access requirements of students with a wide range of disabilities. Blamires (1999) describes the ideal of UDL that focuses on the provision of multiple options for expression, control, engagement and motivation. Loreman acknowledges these principles within the framework of UDL as applied to curriculum design, acknowledging the potential for a unified yet sufficiently flexible curriculum that enables educators to teach in a student-focussed manner (Blamires, 1999; Loreman, 2007).

The reference to ‘design’ in UDL is especially relevant in the education context, particularly for curriculum developers. Those responsible for curriculum design need to be cognisant of students as the ultimate end user. Curriculum development is an ideal place for UDL to be embedded as standard practice. In doing so, curriculum emerges as an interesting and flexible product that offers multiple modes for engagement and assessment.

At the curriculum design stage, UDL encourages accessibility in advance so that there is a greater likelihood for students to learn in inclusive classes where their learning styles, diverse abilities and access barriers are catered for. When embedding UDL principles within the curriculum development process, the diversity of learners, as end users, need to be understood. Consideration of all students incorporates acknowledgement of gender differences, socio-economic status, mother tongue languages, culture, faith, geographic location and disability.

From a disability perspective, UDL aligns with the social model of disability where addressing access is regarded as a social responsibility. This approach recognises that the disability is not the focus but rather attention is on the removal of socially and environmentally imposed access barriers. This includes barriers related to policy, written text, spoken communication and the built environment. All of which can be found in education settings. An increased focus on the identification and removal of such barriers, through the principles of UDL, will result in a more inclusive learning environment for all. Importantly, the removal of such disabling barriers within the learning context, including the curriculum, will reduce the impact of a disability. This approach ensures social structures and systems, including the education system, take responsibility for the removal of barriers to ensure all students feel welcomed, included and are able to demonstrate their full potential.

Despite adherence to the principles of UDL playing a significant role in generating inclusive learning environments, the limitations of UDL cannot be ignored. Even the strongest advocates for UDL such as Dr Frédéric Fovet at Royal Roads University, Canada states that The best of universal design approaches will never eliminate the need for reasonable adjustments for some students.

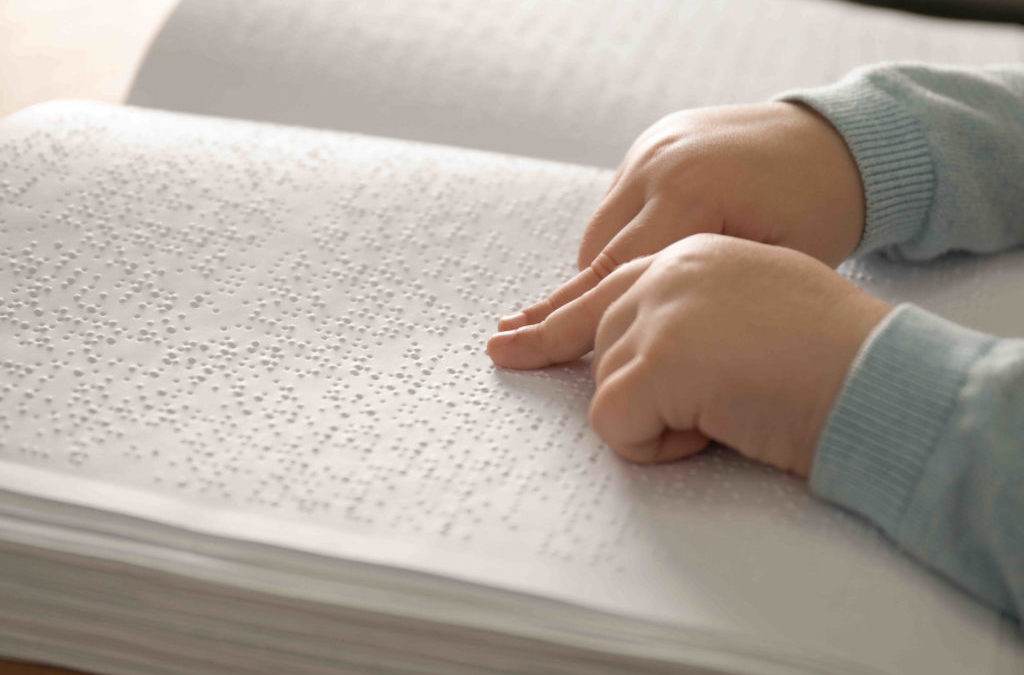

Reasonable accommodations, specific to individual learners, cannot always be addressed through UDL. For example, a student who is blind and requires text books in Braille will receive this adjustment as an individual request. Not all books will be instantly made available in hard copy Braille as there is not the demand nor the resources for developing them. This is not to dismiss the significant achievements of the Accessible Books Consortium (ABC) led by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) who are addressing the significant access barrier to print books for people with a print disability. This work of the ABC is still congruent with universal design principles as it aims to ensure the end user has instant access to alternative format reading material without the need to advocate for an individual adjustment. However, given the current reality that the overwhelming majority of books are inaccessible to people with a print disability, individual accommodations still play a necessary role in access and inclusion.

It is at this point where UDL intersects with the human rights model of disability.

The human rights model incorporates the focus on the removal of socially imposed barriers as in the social model but expands on this position by also recognising the need to provide specific accommodations tailored to individual access requirements. For example, UDL and social model ontology encourages all books to be produced in multiple formats accessible to all. The human rights model, with universal human rights as a starting point, recognises that specific interventions may be required for a child who is blind learning a language to have access to high cost hard copy Braille books alongside access to specific adaptive technology such as a refreshable Braille display in order to access their learning materials. Such specific accommodations are necessary considerations that are often situated beyond the parameters of UDL.

Alternative formatting, additional time and separate rooms for exams and access to specialist assistive technology, typically align with a human rights model and are essential requirements to ensure equal access for some students with disability. This rights-based approach empowers and centralises the voices of people with disability in the determination of the most suitable accommodations to enable their inclusion.

Individual Education Plans (IEPs), used globally to document specific supports not offered within general universal design curriculum and classroom delivery, are an ideal resource to document specific accommodations. IEPs are ideally written by a key disability focal point in the school in conjunction with the student, parents, disability specialists and other people interested in the mainstream inclusion of the child with a disability. The removal of access barriers, adjustments to learning materials and capacity building opportunities can all be included in an IEP.

To genuinely foster an inclusive learning environment, some students may require the development of a range of skills. For example, students who are blind will need to develop skills in independent mobility with a long cane, Braille reading and writing skills and use of a computer with a screen reader. Students who are deaf will need to develop sign language skills. The development of these skills should be written as goals in the child’s Individual Education Plan. This ensures that an individual is also receiving targeted interventions that build their independence and capacity.

A recent scoping study of services for students who are blind or vision impaired in the Pacific documented a case study about the educational journey of a Fijian woman who was totally blind from the age of five. This case study illustrates a range of interventions reflecting UDL principles alongside the disability specific interventions required to ensure her inclusion and success throughout her educational journey. In reading the following case study the strengths and limitations of UDL should become clear. In addition, the significance of inclusion through a human rights model of disability is demonstrated through the student’s opportunities to establish independent skills and access to adaptive technology, accommodations that enabled her to demonstrate her full potential.

Early in Sisi’s life field workers from the Fiji Society for the Blind visited her at her home, providing a variety of early intervention activities. Sisi then attended the Fiji School for the Blind and lived in the school hostel. When at the school, Sisi learned Braille and mobility skills. She then transitioned into a mainstream school from year three. Integration staff from the Fiji School for the Blind visited her mainstream school weekly, providing her teacher with inclusive pedagogical strategies and all of her school books in Braille, Sisi’s accessible and preferred reading format.

By the time Sisi was in her final year of primary school, she was one of the top five students, demonstrating that disability is no barrier to success when provided with the right supports. At high school, students were asked to volunteer as her buddy and Sisi had one friend assigned for each of her classes which worked well in a resource poor setting.

Sisi was then awarded a place in the Bachelor of Education at the University of the South Pacific where she was provided access to a computer with screen reading software. At USP, a group of volunteers, connected through an Expatriate Wives Club, supported Sisi and other students with vision impairments, through regular visits and assistance with reading and research work. She now has a Masters qualification and works in a university as a disability officer, supporting the access and participation of students with a disability. Sisi is a positive role model to others, encouraging people with vision impairment to embrace challenges and not be afraid of moving out of their comfort zone. She stresses the need to “strive for higher things and not limit ourselves to our current situation”.

Sisi’s story demonstrates a positive intersection between UDL through mainstreaming and inclusive teaching strategies alongside targeted interventions such as Braille reading material and access to adaptive technology. The culturally appropriate volunteer supports also illustrate adjustments that can emerge through collaborative practices in a resource poor context.

In conclusion, the principles of UDL are to be embraced and incorporated into every facet of education alongside acknowledgement of the rights and requirements of some students with disability who will benefit from specific adjustments to ensure they have full and equitable access to education. Appreciation of this broader view of inclusion through multiple approaches will go a long way in ensuring no child is left behind and that all learners can demonstrate their full potential.

—

Sisi’s full case study can be found at www.icevi.org/pacific within the recent Scoping Study of Current Services, Resources and Development Priorities for the Education of People who are Blind or Vision Impaired in the Pacific.

References

Blamires, M. (1999). Universal design for learning: re-establishing differentiation as part of the inclusion

agenda? Support for Learning, 14, 158-163. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.00123

Loreman, T. (2007). Seven pillars of support for inclusive education moving from “why?” to “how?

International Journal of Whole Schooling, 3(2), 22-38. Retrieved July 21, 2013, from

Dr. Jo Mosen

Cognition Education Associate, Disability and Inclusion Expert

Dr. Jo Mosen has worked in disability-inclusive education across the Asia Pacific region for over 20 years. Her work spans disability inclusion in primary, secondary and tertiary education contexts, harnessing a strengths-based approach to build the capacity of systems, schools and teachers for the mainstream inclusion of children with disability. She is currently engaged with Cognition Education on a number of programs including work with the Solomon Islands focused on teacher professional development and inclusive curriculum design.