Student voice tell us who they need their teachers to be.

Imagine the impact upon us if we were not able to form positive relationships with our teachers and if those relationships that we did form were mostly negative and even toxic. Yet that is what Maori and other marginalised students tell us is happening to them in their classrooms in New Zealand and in many other places around the world. Student voice explains that the primary cause of these negative and toxic relationships is the way that teachers view them. When students are seen as bringing deficiencies to their learning, rather than value being placed on their prior cultural understandings and ways of making sense of the world, then they experience being marginalised in classrooms. Students’ own knowledge needs to be seen as positive attributes that can be built upon to promote their learning.

There are many marginalised students in modern schools nowadays. Some remain invisible, some are segregated into ‘special’ settings for ‘disadvantaged children’ and some simply absent themselves by their ‘voting with their feet’. These students include the children of Indigenous peoples, migrants, refugee and faith-based groups, children with learning difficulties and children of difference/diversity. The primary effect of these negative and toxic classroom relationships is the marginalisation of millions of students from the benefits that education should be offering them. The secondary and wider impact is the creation of the educational inequalities that plague our schools and wider societies. This means that if we are to ever successfully address educational inequalities, we need to consciously place positive relationship-forming practices at the very centre of whatever we do in education, for unless we attend to this aspect of education, everything else we do will not be as productive as it might be.

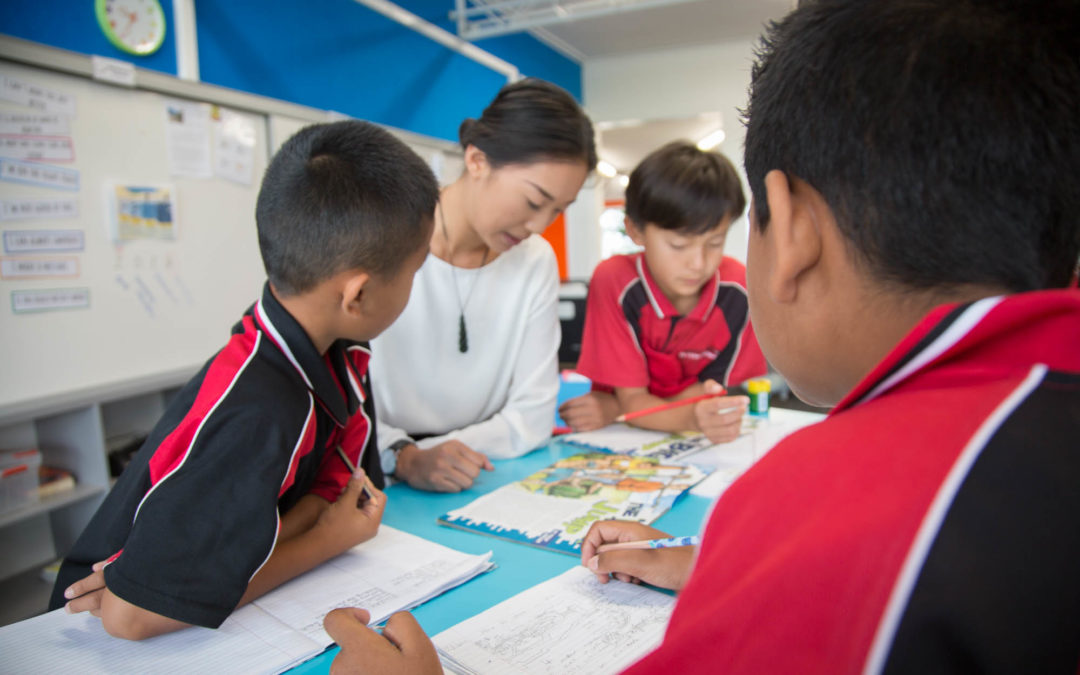

How do we do this? We invoke, in a metaphoric sense, the most important social organisation in the world, the family; for this universal institution provides us with those relational experiences that build our wellbeing, our mental health and our ability to participate in the world on our own terms. Family is the multi-generational collective of aspirations, experiences and practices that creates our connectedness and remains central to our lives. It is in our extended families where we learn to listen and hear, love others, to care for and be cared for, to develop expectations and strive to meet them; where older, more knowledgeable others know what we need to learn and how we best can learn important cultural practices and culturally-generated modes of making sense of the world. To constitute our classrooms as if they were extended families therefore engenders totally different relationships than those that marginalise some learners and promote others. This is what we refer to as creating a family-like context for learning.